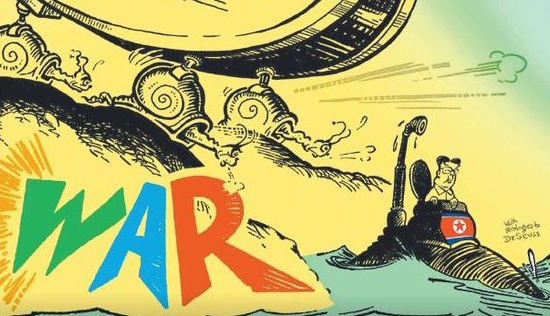

The ABCs of a war with North Korea make bleak reading.

A for Artillery. B for Barrage. C for Casualties (M for Mass). etc.

And if you want to add maths to the lesson try this: 300,000 dead South Koreans and US servicemen, hundreds of thousands of dead North Koreans.

And that, according to experts, would be in the first 90 days of fighting.

Nevermind that it might spiral out of control and suck in other countries: China, Russia… ourselves.

Despite Kim’s ballistic missile tests and Donald Trump’s proclamation to the UN that he is prepared to “totally destroy North Korea” no sane analysis of the situation predicts an attack by either country.

Well before the current crisis over Kim Jong-un’s nuclear programme North Korea had been deemed too dangerous to confront. Bristling with conventional weaponry, as well as possibly chemical weapons, the toll of war with the North had ruled out all but a diplomatic solution.

But with hawkish calls for North Korea to be ‘dealt with’, the US’s UN ambassador Nikki Haley talking up confrontation and Malcolm Turnbull pledging the support of Australia, analysts around the world mostly agree even a precision pre-emptive strike by the US would only prompt a retaliatory attack on the South, and blow up the entire region.

The notion that Kim is crazy and on a death-by-cop style suicide mission over-simplifies the brinkmanship both sides are employing.

Regional security expert Franz-Stefan Gady, of the EastWest Institute in New York, says: “Even without the use of DPRK weapons of mass destruction, civilian casualties in the larger Seoul metropolitan area might surpass 100,000 within 48 hours and that’s just the low-end estimate.

“Many of these casualties would be foreigners including Chinese Australians and Americans.

“US and Republic of Korea forces would shower North Korea with a combination of cruise missiles, bombs, and artillery rounds; Hundreds of thousands of North Koreans would die in this firestorm.

“DPRK would primarily launch WMD missiles against military targets in South Korea and Japan. A special target would be the US bomber force on Guam.”

In layman’s terms it would be like an international version of Waco, but much, much worse.

North Korea has the second largest army in Asia, some 1.19 million troops and another 600,000 reservists. There are 8,600 artillery batteries around the country, most arranged around the demilitarised zone that separates North and South.

Furthermore, war and the termination of trade with the North would fuel a huge refugee crisis, with estimates of a million or more displaced people flooding across North Korea’s border with China.

Of the 150,000 troops the US has stationed around the world, about 29000 are in South Korea and another 47000 in nearby Japan.

Unless the US is prepared to use the doomsday option of nuclear weapons against North Korea, potentially killing hundreds of thousands of people, the only real option is targeted sanctions and a negotiated peace treaty with Kim.

Jingdong Yuan, a North Korea analyst at Sydney University, said the US has no option but to negotiate.

He says: “China could, if it wanted to, have a very severe impact on North Korea’s economy because 90% of North Korean trade is with China.

“But North Korea could then open its border with China to millions of starving refugees. That is why China is not willing to go to that extreme.”

Professor Yuan says Kim Jong-un is sabre rattling to negotiate his own security and, despite the rhetoric, sees the country’s nuclear weapons programme as defensive. Getting the US, Japan, Russia and China to the negotiating table with Kim is vital.

“Right now is not the time to further escalate because there really is no good outcome there,” he said. “Diplomacy, too, will be seen as appeasement. Some specific stringent sanctions are needed that leave enough room for North Korea to see it as incentive to come to the table.”

There have been numerous previous provocations by North Korea that could have prompted retaliation. In 1968 the country’s navy captured the USS Pueblo, killing a US serviceman in the process. There were naval clashes in 2002 in the Yellow Sea and the South Korean corvette Cheonan was sunk in 2010 with the loss of 46 lives.

Since the end of the Korean War there has been no peace treaty between North Korea and the South and its allies. Reconciliation initiatives, such as the 1972 Joint North-South Korean Communiqué, the 1991 Joint Declaration of South and North Korea on the Denuclearisation of the Korean Peninsula, and the 2000 North–South Joint Declaration, all ended with disappointment.

But 64 years after the war ceased, Korea still serves as a buffer zone which separates the economic interests of the China and Russia dominated Eurasian continent from the US-dominated Pacific rim.

American political analyst Robert E. Kelly writes: “So ritualised are North Korea war-scares that the interesting parts are not the rehearsed statements and events themselves, but how people react to them.

“One regularity I have noticed increasingly is the tendency of Western analysts in particular to, for lack of a better word, freak out over North Korea.

“North Korea has this effect. People kinda’ lose their minds and say gonzo stuff they wouldn’t say about other foreign policy problems.”

He says the US has escalated the problem.

“South Koreans are barely paying attention,” he adds. “The South Korean president and then foreign minister both went on vacation in early August, at the peak of the Kim Jong-un – Donald Trump war of words.”

South Korea is used to living with the provocations of the North.

Furthermore North Korea has become an increasingly paranoid state, convinced that it lacks the full support of China and Russia, while potentially being targeted by the US, which conducts annual war games off its coast and stations troops just over its border.

It is worth remembering that during the Korean War, North Korea was effectively levelled.

The US dropped 635,000 tons of bombs and 32,557 tons of napalm on it. Almost every main building in the country was destroyed and the populace effectively moved underground to survive the bombardment.

Of 22 major North Korean cities 18 had more than half their area destroyed. Bombing of Pyongyang was only halted because there were no worthwhile targets left. About one in seven of nine million North Koreans were killed.

And it is against this background that North Korea views the United States.

Kim Jong-un sees having a viable nuclear deterrent as a way of safeguarding his regime, and the speed at which he is developing its missile programme has taken the major powers by surprise.

“It seems that both Koreas are destined to live in the perpetual fear of war without really experiencing it,” opines Dr Leonid Petrov of the Australian National University.

He believes that as well as there being a humanitarian disincentive to take on North Korea, the strategic problems caused by a unification of the divided countries would change the power balance in the region.

Dr Petrov adds: “If the North and South are unified, peacefully or otherwise, the presence of US troops will be questioned not only in Korea but in Japan as well. US security alliance structures across the Pacific will crumble, followed by economic and technological withdrawal from the region.

“Even the new Cold War against China and Russia won’t help Washington prevent the major rollback of American influence in Asia and the Pacific.”

With America out of the picture Russia and China, he surmises, will resume a power struggle for regional hegemony.

“The unification of Korea would open a new era of regional tensions, which nobody is really prepared to endure,” says Dr Petrov.

“If North Korea is deliberately targeted or attacked and destroyed that would trigger processes far beyond our imagination and control and inevitably lead to tectonic shifts in politics, security and economy of the region, which collectively produces and consumes approximately 19% of the global Gross Domestic Product.

“By removing one piece from the current imperfect but undoubtedly stable structure, one risks a domino effect that is likely to come around the globe and hit those who would dare to trigger this cataclysm.

“One needs to be hell-bent on self-destruction to contemplate such a scenario.”

(Originally published in The Daily Telegraph. Illustration by Terry Pontikos)