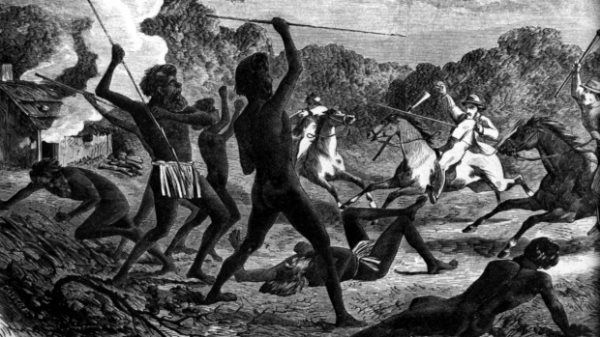

Sometimes they gunned them down or poisoned their bread or water. In other accounts groups were driven off cliffs into deep gorges.

There were many gruesome ways to die if you were an Aboriginal in the ‘Frontier Wars’, which researchers say covered a time from 1788 to well past Federation.

In schools this has been taught as a bunch of disparate massacres – a byproduct of nation-building. Not a war, but a collection of executions of small groups by soldiers, farmers, sealers and various other ad hoc militia.

As poorly as American indians have been treated, US historians have at least painted a fair if unapologetic picture of a protracted, one-sided frontier war on a native population unwilling to cede their land to a superiorly armed invader.

The New Zealand Wars, too, were recognised as a conflict over a legitimate prize – ownership of land and the right to use it.

In Australia we’ve well-rehearsed the presentation of our history from a colonist’s perspective.

From the label terra nullius (nobody’s land) considered applicable to Australia since settlement, to the myth Aboriginals were entirely nomadic when there was plenty of evidence to the contrary (read Bruce Pascoe’s Dark Emu). All of these heavily-weighted descriptions favoured the colonists’ land grab.

The idea of ownership is at the heart of everything our society is built on. To have an asset is to have leverage. Leverage to eat well, to sleep safely, to raise a family and be proud of your place.

Ownership weaves our lives inextricably into the society around us.

Not owning anything is not encouraged in Australia.

And the idea of the indigenous population having no ownership of where they had lived, or of not being organised to defend what they had, is a very convenient perspective.

Professor Jakelin Troy, the director of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Research at Sydney University, laments that the history of Aboriginals in Australia has been taught in isolation.

“Aboriginal massacres have been an open wound since 1788, no one talks about them,” she tells me.

“At least we have a recognition in this country of Aboriginal rights, but we need to teach all the things that have happened.”

To look fairly at the confrontations that occurred when Britain colonised this country, those convenient myths must be stripped back.

That includes acknowledging the indigenous population fought a real war to protect its rights – rights to land, rights to hunt and feed their families. Maybe not an organised war the way the British military would conduct them, but a war nonetheless.

Historian Lyndall Ryan’s ‘massacre map’ which has plotted over 250 such incidents is ample proof that the armed defence by Aboriginals of this land was taking place across the country at hundreds of sites.

You’ve probably heard of the Dharug warrior Pemulwuy, but what about these names: Windradyne, Jandamarra, Yagan or Bussamarai?

They all led a resistance by their tribes to settlers pushing into their territory, and there’s no good reason they shouldn’t be remembered in the same way Americans remember Geronimo, Cochise or Sitting Bull. Heroically.

Aboriginal culture has given plenty to be proud of, but more remains hidden behind this skewed history.

(Originally published in The Daily Telegraph. Illustration of The Battle of Parramatta.)