He boastfully calls himself ‘The Man’ – it oughta be ‘The Mouth’.

Australia’s most controversial sportsman, boxer Anthony Mundine, has a track record of putting his foot in it or, in the Aussie vernacular, shit-stirring.

Accused of racism himself in the past week for effectively telling a fellow Aboriginal boxer that he wasn’t black enough, Mundine came out and laid all his cards on the table over the issue.

The country itself was racist, its institutions were racist and its flag and its anthem excluded Aboriginals, the 37-year-old claimed.

It was the kind of red rag to a bull remark that Mundine is good at making.

In Australia, where he polarises opinion between those that can’t stand that ‘big mouth’ and those who admire a talent that’s seen him win three world titles at two weights, reaction to his comments was quick and mostly negative.

‘Below the belt’ opined one article, focusing on his ill-chosen words to rival boxer Daniel Geale, while an Aboriginal campaigner rather hysterically branded him a ‘neo-Nazi’.

The much-liked Geale, the current WBA and IBF middleweight champion, is a descendent of Tasmanian aborigines, most of whom were wiped out in the 1830s in perhaps the most near to comprehensive genocide ever pursued against a people that we know of.

Mundine at first disputed if there was such a thing as a Tasmanian Aborigine because of that genocide, but later retracted his remarks.

He was accused of shock tactics and several of his sporting peers, Aboriginals included, denounced him and trumpeted the usual line that he should just play his sport and keep his mouth shut.

But Mundine didn’t back off too far and used the opportunity of apologising to turn the accusations around and launch an embarrassing attack on his country’s race record.

In a counter move similar to Australian PM Julia Gillard’s own recent robust attack on the Opposition Leader Tony Abbott’s alleged ‘misogyny’, Mundine told reporters: “Everyone that comes here, and a lot of my close friends and family members, we feel that Australia is one of the most racist countries.

“I want to move forward, I want to unite the people.

”We’ve never had any representation on the flag, yet I see representation of the Union Jack, something that symbolises the invasion, the murder, the pillaging, and on and on. I think we need to address that – it’s dividing Australia, rather than uniting Australia.

“At the moment, I can’t fly it. And I want to fly the Australian flag. I want to fly it for the Australian people. But let’s do it together.”

He went on to describe the national anthem, Advance Australia Fair, as a legacy of the White Australia policy.

He added: ”I think that we need to move forward together, unite together, move forward as people, move forward as Australians, no matter what you are – brown, black, brindle, white – and move forward together.”

What of those comments though? And how valid are they?

Australia’s Aboriginal population is relatively small, 517,000 at the last census, about 2.5% of the population**, with three-quarters residing in cities and country towns, while 25% live in remote communities.

Despite a decent welfare system nowadays the life-expectancy of Aboriginals is about 17 years less than the national average*, a statistic that is twice as bad as comparable nations with an indigenous population.

Unemployment among Aboriginals is three times higher than the non-indigenous population** and Aboriginal women are 58 times more likely to be held in police custody than non-Aboriginals – for Aboriginal men it is 28 times higher***.

Alcoholism, drug abuse, domestic violence and, in some communities, child abuse are endemic problems. The rate that Aboriginals are admitted to hospital, commit suicide or are diagnosed with mental health problems or disease is between two and three times higher than the non-indigenous population****.

All of these facts point to problems that are either not being addressed properly or not being addressed at all.

And the level of indifference to Aboriginals by the non-indigenous population has only begun to turn around in the past decade or two.

In Australia a national Sorry Day has been held every year since 1998 and four years ago the then prime minister Kevin Rudd apologised in parliament for laws and policies that “had inflicted profound grief, suffering and loss” for Aborigines. The previous incumbent John Howard had refused to make an official apology and was backed by about one in three Australians.

Foremost in Rudd’s mind was the controversy over the ‘stolen generation’ of children.

In reality the term used to describe them represented many generations of Aboriginal children, forcibly taken from their families from the 1900s to the 1960s and given to white families to raise in a heartless and bureaucratic attempt at integration.

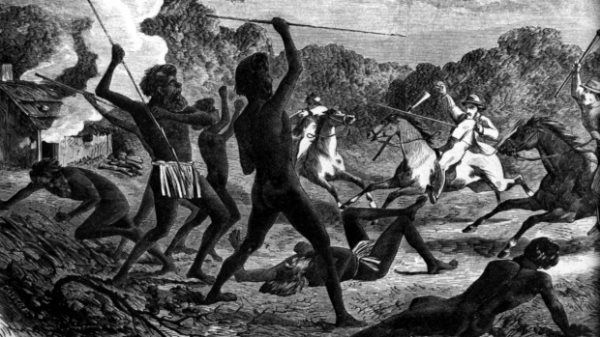

But the apology was also for the numerous bloody, one-sided massacres committed by settlers, whalers, sealers, police detachments and the British armed forces, carried out since the early days of colonisation right up until the late 1920s.

While the benefits system is now supportive of Aboriginals, they were not entitled to a pension and other welfare until 1959.

It was not until 1962 that Aboriginals nationally were given the right to vote and it was only made compulsory, in line with the non-indigenous population, in 1983. There were bans on Aboriginals entering some town centres, right up until 1948 when the Western Australia capital Perth finally relented.

Among Mundine’s incendiary comments was the claim that Geale didn’t represent the Aboriginal community, citing his ‘white’ wife and kids.

He told a press conference for the fight: “I don’t see him representing black people, or coloured people. I don’t see him in the communities, I don’t see him doing the things I do to people, and fighting for the people. But he’s his own man. He’s got a white woman, he’s got white kids. I keep it real, all day every day.”

To outside observers it was a bit like Muhammad Ali’s portrayal of Joe Frasier and George Foreman as white stooges, part trash talk, but with the kernel of a real issue buried far beneath.

Explaining it later he added: “I wasn’t attacking her (Geale’s wife), or attacking her race. My outlook is, as an Aboriginal man, our people, we’re probably the most endangered species. We’re a dying race, and we’ve just got to embrace our sisters. There’s too many footy stars and too many other stars in powerful positions that don’t. And I don’t know why. That’s how we’re going to keep our people going.’

“Our women are the backbone of our community, and the Aboriginal community is weak if our women are weak, we need to bring our women up with us and embrace that.

“Our mortality rate is far worse than our birth rate. We are probably one of the only races on Earth like that right now.”

As crass as it seemed to direct those comments at the amiable Geale it was the type of view once espoused in 1960s America by Black Power activists – respect the sisters, nurture your own race, don’t fall victim to trying to meet the expectations of the majority.

Mundine has been attracting attention since the early 90s when he had his first amateur fights aged 17.

A top junior rugby league player at the time he was also the son of Tony Mundine, a fearsome hard-hitting Aboriginal middleweight boxer who had fought the legendary Carlos Monzon and ‘Bad’ Bennie Briscoe among others.

From an early stage in his life there was some air of anticipation about what Anthony Mundine would achieve, having already been earmarked as a gifted athlete in at least three sports (there was talk of him playing in Australia’s National Basketball League).

Since those early mutterings of potential Mundine’s won 44 fights and given up a successful career in rugby league, where he represented NSW in the game’s teak-tough State of Origin series.

He’s now 37 and, perhaps too late, is trying to attract some big money fights in the U.S. where it’s taken more than a decade for the heat to go out of acrimony at remarks he made blaming the country’s foreign policy for the 9/11 attacks.

And the Mundine mouth has continued to see the boxer run foul of the press and public.

But Aboriginal Australians need champions and not just successful sports people that tick all the right boxes for the white community. They need individuals with a profile that are prepared to speak up.

Mundine may not be the most eloquent orator, and he may not be the obvious choice as a mouthpiece for political change in Australia, but maybe he has a decent point or two to make.

Does that dour Federation-era anthem reflect anything about Australia today?

Should the country keep flying one of the many identikit flags that dot the South Pacific featuring the Union Jack in the top corner?

And do its people care enough about the Aboriginals to improve their life expectancy and their general well-being to a point equal to their own?

National Sorry Day (now called the the Day of Healing) is worth nothing if it’s just an apology for a distant past.

If Aboriginal kids continue to grow up with few opportunities and little self-esteem what good is saying ‘sorry’ to make ourselves feel better?

More people like Mundine are needed to start talking about solutions.

And not just Aboriginals – white folk too.

* Australian Institute of Health and Welfare

** Australian Bureau of Statistics

*** Australian Institute of Criminology

**** The Medical Journal of Australia

(Originally published in The Huffington Post)