In Britain a debate is raging over what constitutes anti-Semitism after it was reported Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn had attended an event eight years ago where Israeli policies towards the Palestinians were compared with the Nazis persecution of the Jews.

At the event Corbyn attended, controversially on Holocaust Memorial Day in 2010, the comparison was made by Hajo Meyer, a Jewish survivor of Auschwitz, and one of many Jews who are supportive of the Palestinians and critical of Israel’s treatment of them.

As some use the stigma of anti-Semitism to quash any criticism of Israel, it’s a valid but highly volatile area of discussion.

The charge of hypocrisy by Israel has arisen on and off over the years in reaction to events in the Occupied Territories and the inability of some to marry the idea of a people who went through the Holocaust carrying out what, at times, have appeared oppressive acts or heavy-handed reprisals against another people.

The Israelis have always argued it is necessary to ensure their security, a position they arrived at after all their neighbours attempted to drive them out of the region.

There are two distinct sides to this coin.

But let’s firstly be completely clear on any comparison with the Nazis during World War II.

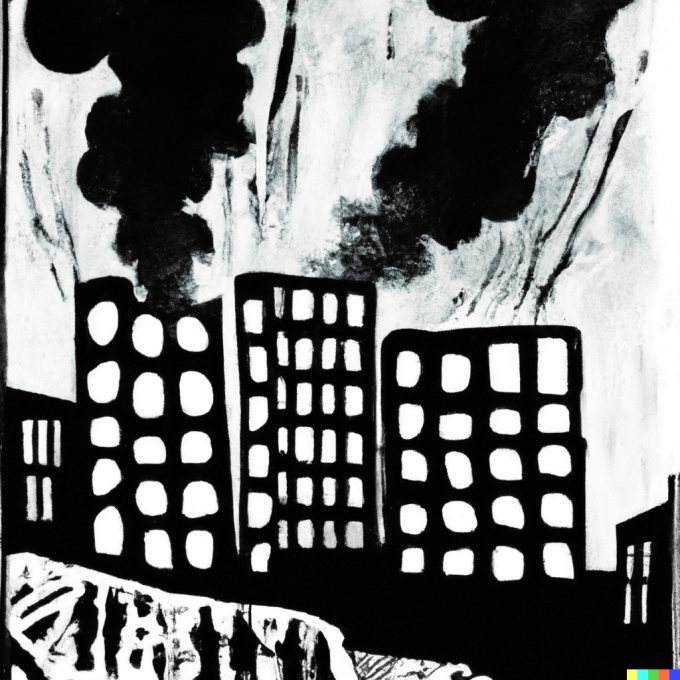

The Holocaust not only ended the lives of six million Jews, it involved a level of dehumanisation, of maltreatment and torture that is still today difficult to put into context with what we know people are capable of.

There have been genocides that have killed more and particularly sadistic individual crimes that bear comparison, but not to the level conducted by the Nazis.

The treatment of prisoners of war by the Japanese in the Pacific or their murderous sacking of Nanjing, while similar, again, were not the extensively drawn out, top to bottom assault on hope, health and happiness endured by Europe’s Jews.

The word ‘evil’ is overused, but not in the case of the Nazis. Their actions defied the very definition of human.

While there are valid grievances about Israel’s part in virtually incarcerating the Palestinian people in Gaza and the West Bank, the building of illegal settlements and the refusal to allow the return of refugees, they do not compare with Nazi Germany.

That doesn’t, however, in any way devalue the suffering of people such as Palestinian refugee Olfat Mahmoud. We feature her story this week, a long fight for repatriation to her homeland.

But we also tell the tale of WWII photographer Mike Lewis, who documented the horrors that the liberating British and Canadian armies uncovered at the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in 1945.

Modern-day Israel is a state with a fortress mentality, an “us versus them” ethos, that has been forged as much by the anti-Semitic treatment of Jews during, before and after WWII, as it has been by the Arab-Israeli wars.

But being supportive of both Palestinian rights and of Israel are not mutually exclusive positions. A fair outcome for both is still achievable and some day will happen.

The danger is allowing the discussion to be dominated by extremes.

The Nazis were evil. Of that there can be no doubt.

The Israelis and the Palestinians, while at loggerheads now, are normal people, with normal fears, normal hurts and a mutual need for a safe and shared future.

(Originally published in The Daily Telegraph)