Power shifts in the Middle East are rarely subtle (often they’re accompanied by large explosions), but their true motivations are usually complex and, quite often, well-concealed.

We’ve got used to disruption and death in that part of the world. We shouldn’t have.

There has been an unconscionable meddling in the affairs of countries in the Middle East, but there is also the danger those tactics will be expanded elsewhere.

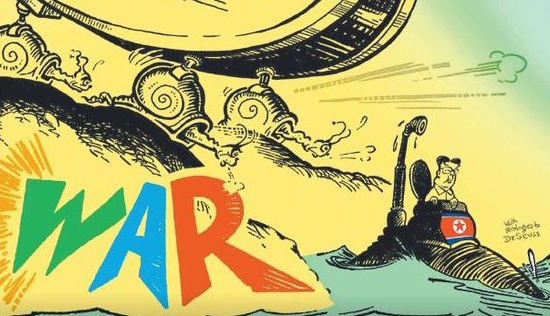

One of the most sinister propositions yet has been the US talking openly about the ‘Libyan model’ in reference to North Korea.

It refers to regime change by force, leaving a shell of a country to fight among itself, rebuilding by foreign contractors (lining their pockets), little aid and less attention.

“That was a total decimation,” US president Donald Trump said candidly yesterday.

Before the violent unseating of Colonel Muammar Gaddafi, Libya was the most prosperous country in North Africa and by most measurements stable.

With attacks by foreign-backed rebels it descended into what the West was quick to label “civil war”, but was actually Libya fighting a small insurgency in one pocket of the country.

Claims by NGOs and rebels in 2011 that Gaddafi’s military was massacring civilians by shelling towns were ultimately proved to be untrue. But they provided the pretext for the US to push for a UN Security Council mandate enforcing a no-fly zone to protect civilians.

As a journalist working on a Fleet Street tabloid at the time I fielded many nightly reports from the ground of rebels breaking the ceasefire as the Libyan military stood back.

And yet it was the claims of the US government that Gaddafi was responsible that became the accepted narrative in the media.

The UN mandate was then cynically used by a coalition, led by the Americans, British and French, to bomb the Libyan army into submission and create a corridor for the rebels straight to Tripoli.

By the end of 2011 Colonel Gaddafi’s brutal, undignified murder by those rebels had been videoed on a phone and shared around the world, and Libya had descended into hell.

Today, the country is divided between two competing governments and a variety of Islamist rebel and tribal groups recognising no authority.

In other words, it is a compete mess. And for what?

The ‘Libyan model’ that Donald Trump and his national security advisor John Bolton speak of does not provide solutions, only worse problems. And a compliant and gullible media has done itself no justice by accepting unfounded claims as fact.

Take a closer look at how much actual evidence (as opposed to claims and unverified intelligence reports) has been presented that the Syrian government is responsible for chemical weapons attacks.

It may surprise you.

Former US president Barack Obama has been pilloried for derailing a budding war on Bashar al-Assad, and allowing Vladimir Putin time to sneak in and provide a permanent and effective deterrent against any significant military action by the US.

But the truth is Obama’s defiance of his own State Department saved Syria from an even more bloody and pointless period of destruction than currently exists there.

Ousting Assad and leaving the Syrians to the fate of the jihadist groups that would fill the void would have created another Libya.

Whereas Obama’s policies sought to create more balance in the Middle East, a deal to stem Iran’s nuclear program balanced against the anti-Iranian alliance between Israel and Saudi Arabia, Trump has ripped up the 2015 deal with the mullahs and given his material support to Benjamin Netanyahu.

The message to everyone across the region is the US is on the front foot in the Middle East. It has already shown with Syria it will push to the point of risking a fight with Russia.

So, the US’s canonisation of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital this week, while further stifling the hopes of an independent future for those incarcerated in Gaza and the West Bank, was really about ratcheting up pressure on Iran, where Bolton would also like to see regime change.

North Korea doesn’t need the ‘Libyan model’, nor does Iran, nor does Syria.

But is it coming? Stay tuned.

(Originally published in The Daily Telegraph. Screenshot of Colonel Gaddafi’s death)