Alex Blackwell’s brow furrows. The heavily pregnant (her baby is due in five weeks when we meet) TV commentator and former Australian women’s cricket captain has just heard her friend Beth Mooney has had her jaw broken. On the eve of the Ashes series, the loss of Australia’s best batter is bad news, but it’s more Mooney’s immediate health that is bothering Blackwell.

“She needs surgery,” she informs me, checking a stream of phone messages from friends and contacts. I ask how it happened.

“Motty [coach Matthew Mott] was throwing to her [not bowling, but chucking down deliveries in the practice nets],” she responds matter-of-factly. “Apparently, it came up under the grill [face protector]. She was a big support to me in that 2017 tour and an avid reader… I’ll send her an advance copy of the book.”

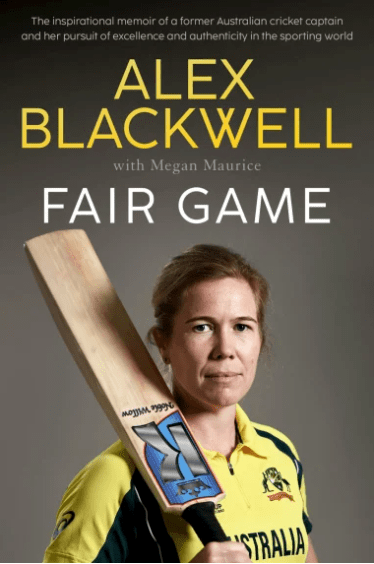

The book in question is Blackwell’s memoir, Fair Game, which is published this month. I commiserate dutifully and motion to the waitress for a menu, as Blackwell texts a salvo of replies. (Mooney returned to the crease just nine days after having surgery on her jaw.)

We’ve met at Lavana on Sydney Harbour. It is a place neither of us has dined at before but, because of COVID-19 infection numbers (29,833 cases the day of our assignation), it is the product of a search for an à la carte restaurant with open-air seating – not that simple a prospect for lunch on a Tuesday. There’s a light rain that comes and goes and the sky’s a comforting shade of grey, as we relax into the woven-backed Parisian bistro-type chairs.

Between its awnings and folded away front and side windows, Lavana is breezy and fresh, and the old wharves of Walsh Bay and their expensive pads float on the sea before us.

After conferring over the menu, we decide on Pelmeni (Russian-style chicken dumplings) and seared scallops as a starter to share. I tell Blackwell “no judging” on the matter of drinks, but she pats her stomach and orders mineral water anyway. Showing zero solidarity, I choose a glass of Cesari Pinot Grigio Delle Venezie, a crisp, dry and light Italian, with a slight grapefruit finish.

We’re seeing young boys looking up to the girls. They’re attending these matches, they don’t see gender.

“I’m looking forward to getting active again,” she tells me. “I’m having difficulty walking and feel uncomfortable in my body. I used to be an elite athlete and recognise how fit I was now that I’m not.

“I’m starting to think I’m two people, not one, and my mum is thrilled I’m not on the road [cycling to work] any more.”

Blackwell retired from international cricket four years ago and now commentates on TV. She also consults as a list manager for the Sydney Thunder – the Women’s Big Bash League team she led until 2019 and which she left owning the record for most runs and games across both the women’s and men’s competition.

A right-handed specialist bat and sometime medium pace bowler, she plundered 14 titles with the NSW Breakers, averaging over 47 with them. She held the record for most international appearances by an Australian woman player (251) until Ellyse Perry passed her in October. And, was the first woman to be elected a director to the board of Cricket NSW.

The 38-year-old’s next accomplishment will debut a month before that of Blackwell’s identical twin, Kate, who is pregnant too, with her first baby. She tells me the sisters, who both represented Australia in cricket and now share an obstetrician, are not that alike – but I’m having a hard time buying it. They are set to join a burgeoning baby club of Australian international cricketers becoming mums, including the current vice-captain, Rachael Haynes.

Blackwell has watched the game explode as better marketing and more cash has increased its visibility and appeal.

“We’re seeing young boys looking up to the girls,” she says. “They’re attending these matches, they don’t see gender and they’re getting photos with legends. There are young boys now modelling their game on the likes of Meg Lanning.”

Blackwell is on maternity leave from NSW Health, where she works part-time as a genetic counsellor, while juggling other commitments. It’s timely not just for the baby but also the publicity drive for the book.

Fair Game, written with journalist Megan Maurice and published by Hachette, recounts her early life, her rise up the ranks of female cricketers, and the triumphs and disappointments she faced as a player and a lesbian, in a time when people in the LGBTQI community had little support. The book’s title says it all and although, for Blackwell, it draws a line under many things, it is going to put a few noses out of joint.

“The views expressed in the book will not come as a shock. I think it’s important to speak directly to people about your issues… and I’ve done that,” she says bluntly. “We should be scrutinising what goes on in our national team.”

And what does go on in the national team she hasn’t always been happy with, slating simplistic tactics, a stifling of creativity and the patronising of female players by Cricket Australia and some of its coaches.

During her playing career, she was often at odds with coaches’ strategies and has some firm thoughts on the current set-up.

“I see fewer genuine batters coming through and I’m fascinated with the leg-spin bowling selection,” she says. “Alana King is great, but I wonder why we don’t have a ripping legspinner in that team. We want to encourage our spinners to turn the ball. I think Wello (Amanda-Jade Wellington) is just a bit of a different cat. I think we should encourage them to explore all their talent.

“It’s a bit robotic to pick people that only attack the stumps. It’s like, ‘We’ve cracked the code and there’s only one way’.”

My heroes were not women originally because they were not on television.

Despite this, she sees Australia winning the multi-format Ashes, but predicts a close series. (Correct, as it turned out, with the Ashes retained last night in the first ODI).

Blackwell was born in the NSW Riverina town of Wagga Wagga, 10 minutes before Kate, and grew up on a farm in the town of Yenda with her two older sisters, Leigh and Jane, and supportive parents who, she says, “wanted a rich life for their daughters”.

It was with Kate she first learnt to play the game on their grandparents’ wheat and rice farm near Tharbogang, just outside Griffith, using an old tree stump as a wicket.

“The champions of women’s sport and women and girls in sport tended to be males out in the country for Kate and I,” says Blackwell. She honed her craft on the concrete pitches of the Griffith Exies Club, across the road from her school. It was there that a teacher, noting their talent, set up the first female cricket team at the school. Within the year it had won the state knockout and Alex and Kate came to the attention of Australian cricket captain Belinda Clark, the country’s most decorated exponent of the game.

From that point on, Blackwell had the sport in her blood. While studying medicine at UNSW, she made her debut for Australia at the age of 19. Kate followed a year later, the pair being compared to the Waugh twins, Steve and Mark, who in 1991 had become the first twins to play test cricket for Australia.

“My heroes were not women originally because they were not on television,” she says. “It was only when I received a poster of Belinda Clark that I realised women played.”

“It irritates me when I hear, ‘Oh, how good’s the women’s game now, how quickly is it improving.’ The men’s and women’s games have always been improving and I feel it’s disrespectful to the legends of the game that came just before TV [picked it up].”

It is not the only criticism Blackwell has for how women’s cricket has been treated or of cricket’s authorities. Fair Game details her disappointment at being shut out of full-time Australian captaincy and the initial lack of encouragement for acknowledging LGBTQI players. But the experience, she says, taught her a lot.

“One of the lessons I’ve learnt is you aren’t always going to be number one choice for a role and that’s OK,” she says. “You can do a very good job in 2ic [second in command]. That’s the position I found myself in a lot.

“I do feel the attributes that made me good as a vice captain were held against me to be the actual captain… People can be pigeonholed in that deputy role and I felt a little bit that nice guys finish second.

“You have to put yourself forward for these positions and I didn’t put myself forward fully when I really had a great opportunity to be the number one leader in the team. If you do want to step up you need to demonstrate that.”

But Blackwell also acknowledges a tightrope walk for ambitious women, adding: “Women leaders need a lot of likeability to make it to the top.

“What I’ve learnt around leadership is it takes time to embrace different views, but if you don’t, then you run the risk of missing things. If I was the leader or coach of the best players in Australia I would want them to have more ownership of the direction.

“It felt at times under coaches from the men’s set-up coming into the women’s set-up that there wasn’t enough trust and respect that those players know their game and should be directed.

“I thought that hurt us in the end. Because I feel people rise or fall to the expectations you put on them and if you’re only going to plan for one thing you’re never able to get out of trouble if that’s not working.”

Professionalism in domestic women’s cricket has had an obvious impact on the game and, with better production and marketing, made stars of the current crop of cricketers. But the pioneers behind that change can be found in only low-res video on YouTube.

“Women being able to play longer has allowed the game to improve,” says Blackwell.

Although parity for female players has improved, there’s much work to be done. Blackwell herself made enough to play as a professional for only six months of her career. She and her wife, former England player Lynsey Askew, now a personal trainer, live in a nice two-bedroom apartment in Ashfield, but it’s a far cry from the likes of David Warner Inc and his collection of multimillion-dollar residences.

Blackwell struggled from a young age with, what she calls, her own internalised homophobia that “chipped away” at her. She recounts being told pointedly by a Cricket Australia official that the organisation was promoting the game as “a place mothers wanted to bring their daughters to play” and not to talk about being gay.

There’s still some moments where that internalised homophobia rears its head. It’s a response to growing up in Australia and growing up in cricket.

Despite these slights, in 2013 Blackwell became the first woman international cricketer to publicly come out as lesbian.

“Growing up in a society that has those subliminal messages was hard, and it’s still not always easy for me,” she says. “People will look at me and think, ‘Oh, she’s out there and proud.’ But there’s still some moments where that internalised homophobia rears its head. It’s a response to growing up in Australia and growing up in cricket.

“I’m OK with the person I’ve become and I like who I am, and it was difficult to feel my sport didn’t want me.”

The book is full of Blackwell’s clashes over prevailing attitudes. But, pragmatically, she rarely allows herself to respond emotionally, instead resetting when ruffled and presenting a calm, rational argument. What Blackwell hardly ever does, however, is leave things unsaid.

“I’m a little bit fatigued by that actually,” she says, as our mains arrive: pan-fried barramundi for her, duck a l’orange with baby carrots pour moi.

I put it to her that she might be “a bit mouthy”. She pauses, then laughs, seemingly in agreement. The truth is Blackwell is not a confrontational person, but determinedly finds ways to get her point across on her own terms.

“I think I’m always someone who’s looking at how can we be better, how can I be better and that puts pressure on other people,” she says.

With Askew, her partner of 13 years, she is now contemplating a whole new phase of life. But interestingly, that life remains closely entwined with Kate.

“We’re not in the same hospital,” she tells me, struggling to illustrate they’re not as in sync as it appears. “It’s a totally new phase of my life now. I’m so excited about it.

“[Kate’s] due a month after me. Isn’t it ridiculous? It’s just silly. We’re both 38, so we’ve got to get on with it. We’re really not that twinny, we’re not that twinny at all.

“We’re a little different with our [hospital] preferences, but we are seeing the same obstetrician. I told him, ‘You’re going to get us mixed up, we’re both in same-sex relationships, one month apart.’

“It’s going to be good going through this new challenge together. We’ve always lived our own lives but as it’s turned out, we’ve had similar interests. I’ve been very lucky to have her. She’s almost been like a psychologist to me.”

Blackwell is part of a baby boom recently among Australia’s female cricketers. Haynes and partner Leah Poulton had a son in October. Fast-bowler Megan Schutt’s partner, Jess Holyoake, had a daughter in August. And last month, former international and current Australia A player Erin Burns’ partner, Anna Jane, gave birth to a boy.

That’s been very powerful. To have a position where I can influence and I can speak up – so I’ve done that and don’t hold back any more.

Will there be a baby club?

“Probably,” says Blackwell. “Rachael and Leah are very good friends and live not that far from us.”

It’s a long way from the days when gay players trod awards night red carpet events alone, afraid they could lose their place in a team or even their job if they were “out”.

“It was a big deal for me to actually say, ‘my partner’ for the first time,” says Blackwell. “I accidentally found myself in this position – rocking the boat. These days through the medium of social media there is no coming out any more. You just put up a picture of yourself out to dinner or getting engaged and it’s just out there. I think that’s great. It’s just not such a big deal any more.”

But what she went through, and more so, what past players went through, is a source of anger for Blackwell. She believes an official apology is due to players intimidated into hiding their sexuality.

“I have connected quite a lot with past players, just randomly, who come up to me and say, ‘Thanks for saying what we couldn’t.’ And that’s been very powerful,” she says. “To have a position where I can influence and I can speak up – so I’ve done that and don’t hold back any more.

”I feel like the invisible legends have paved the way and given so much against the tide. I can’t speak for them, but my perspective on what they’ve done is huge and they didn’t get to enjoy the freedoms the current players do. I feel sad about that.”

As we finish off the meal with apple crumble and lava cake with ice cream, splitting them down the middle to share, it’s only the future Blackwell has her eyes on.

And she gives a big steer to the gender of her baby in the book’s last chapter (you’ll have to buy it).

“I’ll definitely take our child to the nets someday and see what they think,” she says, “we will bring a lot of love to that child.”

First published in The Australian Financial Review on February 4, 2022.

Image of Alex Blackwell by Bahnfrend Wikimedia Commons.